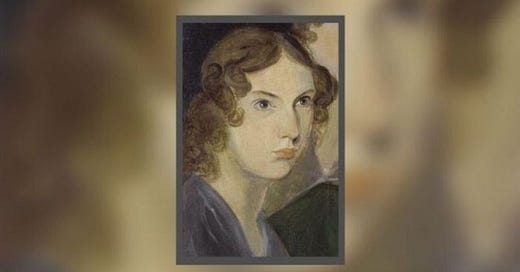

The tragic story behind Anne Brontë's final resting place

Why the youngest Brontë sister ended up buried miles apart from the rest of her family

Haworth is a small town in the north of England, famous for being home to the Brontë family in the 1800s. It is also the birthplace of Charlotte, Emily and Anne’s famous novels, including Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. The town is a popular tourist attraction, and visitors come for romance, inspiration and nostalgia. There…