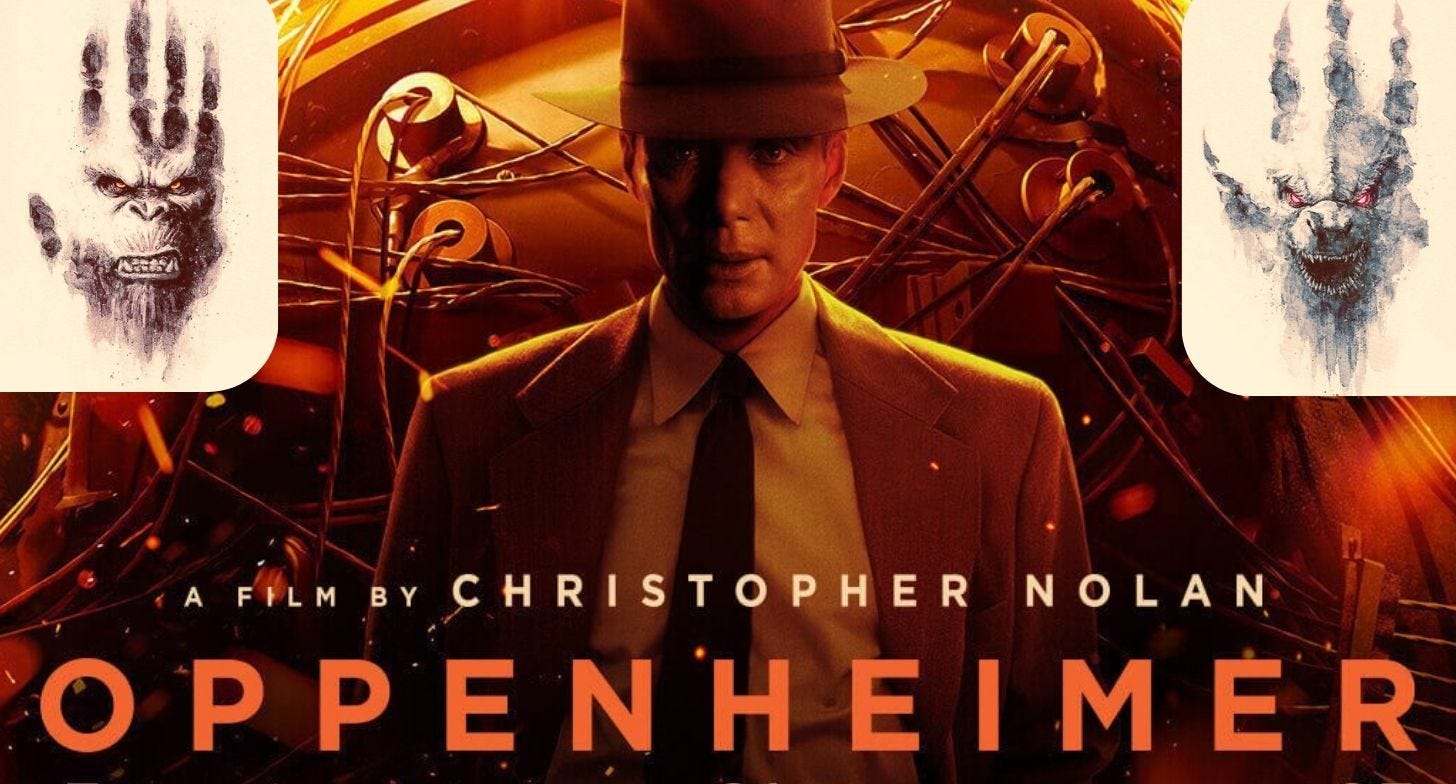

Years ago, I surprised my friend Fi by suggesting we see Kong: Skull Island at the cinema. She indulged me and we spent most of the movie giggling our heads off at a) the randomness and scale of it all and b) the fact we were there of our own volition watching it. This has now become a tradition, so of course when Kong x Godzilla was released on Wednesd…

© 2025 Sara Foster

Substack is the home for great culture